Whether experimenting with Afrobeats and Western rap or debuting groups with mostly non-Korean members, K-pop is transforming to reflect the diversity of its global fanbase. But what does this mean for the industry’s future and what are the key takeaways from K-pop going global?

One of K-pop’s most anticipated debuts of 2024 is VCHA, the brainchild of Republic Records and JYP Entertainment.

Their debut single, “Girls of the Year”, contains all the hallmarks of what we know to be quintessential K-pop — high production value, tightly choreographed dance formations and ridiculously catchy pop hooks.

But newly debuted K-pop groups are bringing a surprising twist to the music scene, leaving fans buzzing with excitement and confusion as they try to comprehend what comes next.

Upon closer inspection, VCHA is defying the industry’s mould of what a K-pop group looks like.

For starters, the group performs in English and promotes both in South Korea and the US with members forming a patchwork of diverse backgrounds and reach.

Leader Lexi, 17, is Hmong-American while Quebec-born Camila, 18, is Cuban. Meanwhile, Kendall, 17, is of Vietnamese descent and hails from Texas while Savanna, also 17, is Venezuelan-Trinbagonian and was raised in Florida. KG, 16, is possibly the first white K-pop idol to debut under the Big Four K-pop companies and Kaylee, 13, is the sole member of Korean descent.

A group like VCHA may seem unheard of according to K-pop norms, but they are just one of the many groups bursting onto the scene that have an explicitly global positioning.

Take Hori7on, the first Filipino K-pop boy band that performs in Filipino, English and Korean. Then there’s XG, an all-Japanese girl group that’s taking things up a notch: they’re based in South Korea, trained under the K-pop system by a former idol turned producer and sing entirely in English.

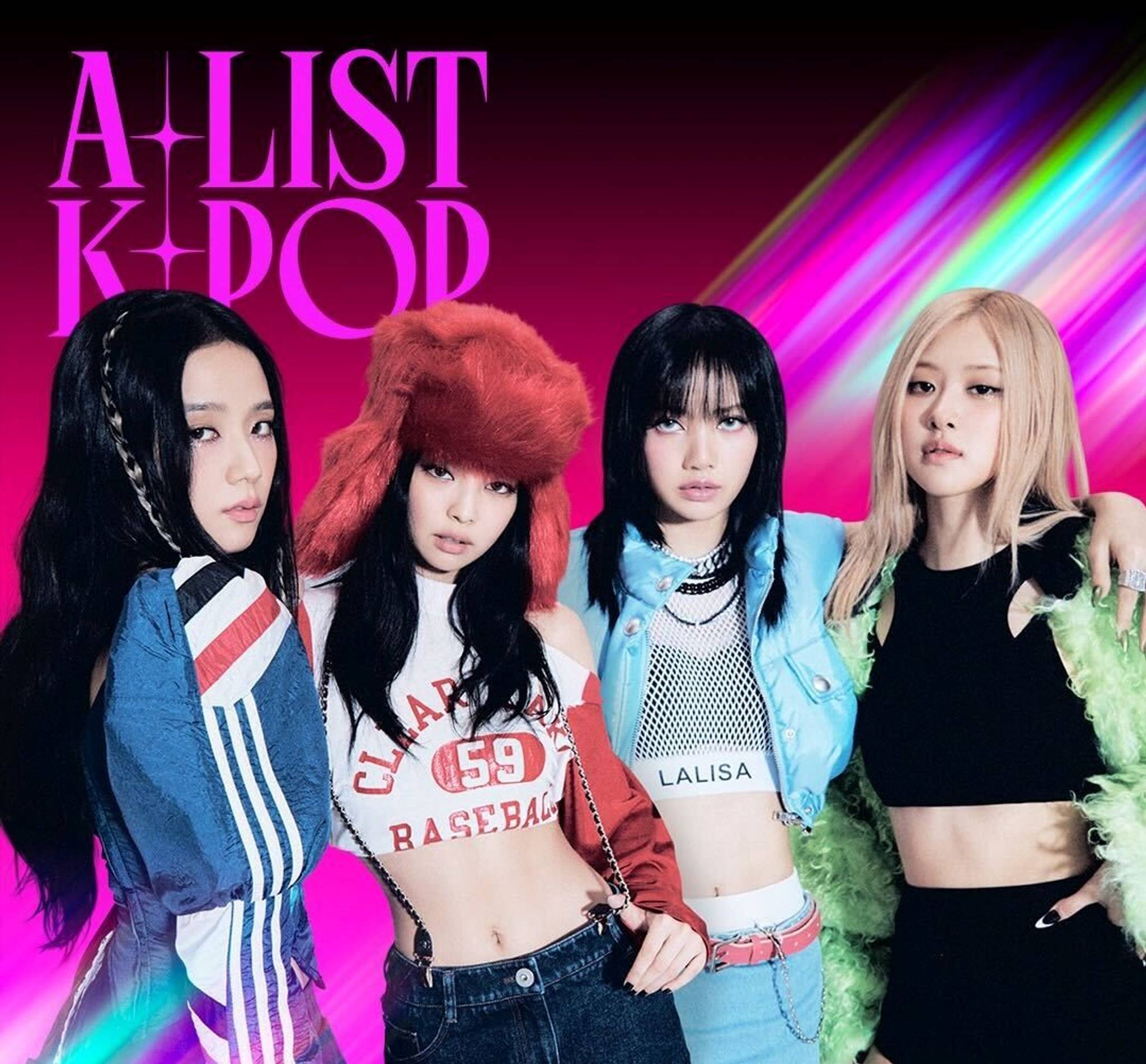

And not to forget Blackswan’s Senegalese rapper Fatou, who defied industry norms to become the first African K-pop idol, and British K-pop boy group SM who are set to debut in 2024.

While the reception to this new wave of K-pop icons has been largely positive, some fans are discomforted by the rapidly changing face of the industry.

Tensions had already begun to rise when major acts like BTS, TWICE and aespa began pivoting to full English-language releases. Jon Caramanica, the New York Times’ pop music critic and host of Popcast, sparked an intense online backlash after insinuating that BTS member Jungkook’s ‘main pop boy’ image à la Justin Bieber “ceases to be K-pop at all”.

Some BTS fans — also known as ARMYs — felt that such criticisms framed K-pop through the lens of the Other, where artists are defined in opposition to Western sensibilities under an exotic gaze.

Non-Korean idols have also been subjected to racist or xenophobic comments from anti-fans. “You aren’t Korean so [you’re not] K-pop, sorry but this is the truth,” says Instagram user @tiny_prettyjeon_ when VCHA first teased their pre-debut single.

But clinging onto purist ideas of what K-pop should look or sound like is at odds with the industry’s creation which is indebted to the global music scene — and Black music in particular.

The birth of K-pop as it is now known can be traced to Seo Taiji and Boys’ 1992 hit single “Nan Arayo (I Know)”, where its unique blend of hip hop, new jack swing and breakdancing forged an artistic blueprint that would shape the industry for generations to come.

Today, a melting pot of niche, multicultural genres like neoperreo, Miami bass and Afrobeats are firmly embedded into K-pop’s sonic DNA.

And while the industry’s constant borrowing from non-Korean cultures has also sparked uncomfortable yet necessary dialogues about the longstanding issue of cultural appropriation, K-pop’s increasingly fluid identity is expanding beyond ethnic, linguistic and national lines.

So what does this mean for K-pop's future?

Well, things are looking bright on the K-pop scene as even the Korean government seems to be pivoting towards a more diverse vision of K-pop’s future.

In a bid to cash in on fan-driven tourism, the Hallyu visa makes it easier for non-Koreans to register as K-pop trainees which could open the floodgates for more foreign K-pop idols down the line.

As transnational fandoms come to the fore, championing diversity in meaningful, nuanced ways while remaining attuned to what makes K-pop so appealing is keeping its spirit alive.

After all, there’s always something for everyone in K-pop regardless of genre, language, age, gender and sexuality or ethnicity.

Expanding K-pop's global allure isn't just about catchy tunes and mesmerizing choreography; it's a harmonious fusion of cultures, transcending borders and connecting hearts worldwide.

And that's what makes it so appealing.