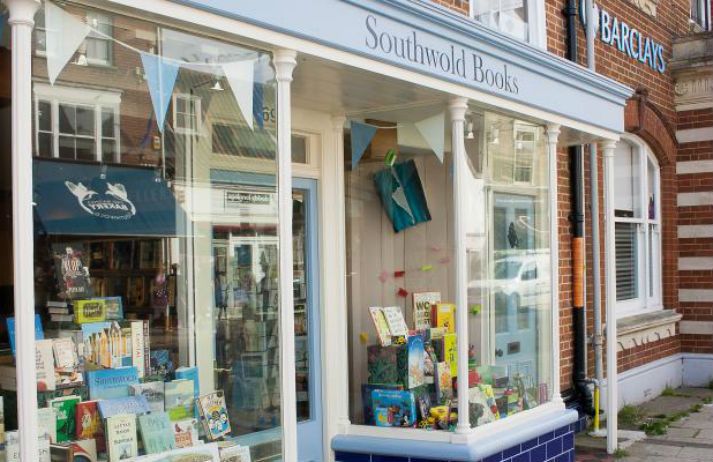

Have you ever visited Southwold Books in Suffolk? Or Harpenden Books in Hertfordshire? They might sound like family-owned independent book shops, but they’re actually ‘incognito’ stores from Britain’s biggest bookstore chain Waterstones. And the locals aren’t happy. We explore the insight behind these unbranded stores, and understand why flying under the radar can sometimes prove beneficial for brands.

The unbranded stores have opened in the towns of Southwold, Rye and Harpenden, with a handwritten notice in the window indicating that they're part of Waterstones. But while locals are calling ‘subterfuge’, managing director James Daunt claims it’s all about managing expectations. “What people expect when they see the brand is a lot of books,” he says, “but when you walk into something no bigger than a London bus, then it has got to be different.” And since there isn’t the real estate to open larger stores – the smallest Waterstones outside of these branches is 2,500-square-foot – indie stores were the solution.

But at a time when people value authenticity and covet the inclusivity of an ‘indie brand’, the move has potential to improve business – a fifth of UK consumers say they shopped at independent retailers more in 2015 than they did in 2014, with 13% saying that they actively try to bring their business to such retailers. “Indie is, at once, a genre… an ethos, a business model, a demographic and a marketing tool,” says Rachael Maddux, author of the essay ‘Is Indie Dead?’. “It can signify everything, and it can signify nothing. It stands among the most important, potentially sustainable and meaningful movements in… popular culture – not just music, but for the whole cultural landscape.” In short, it’s a lifestyle that people can buy into.

But Waterstones’ move has already sparked cries of dishonesty. With nearly two-thirds of people claim not to buy from companies they don’t trust, that doesn’t bode well. Tesco similarly found itself in hot water after it named a number of own-label brands – like Rosedene Farms – after farms that don’t exist. While the supermarket claims the names were intended to insinuate quality, instead they were condemned as misleading. Will people similarly be put off shopping at Waterstones as they become aware of this masquerade?

Charles Pickering is a researcher at Canvas8, which specialises in behavioural insights and consumer research. He previously completed a Master’s degree in cognitive and evolutionary anthropology at Oxford, and loves a good dataset.