Aesthetically perfect, gunslinging androids and an endless supply of creepy, philosophical questions stand at the frontline of HBO’s latest offering, Westworld – a televised remake of the eponymous ‘73 movie. And they’re effective draws – the first episode lured in 3.3 million viewers, more than the debuts of True Detective and Game of Thrones. But just like all of the most appealing (and memorable) science fiction, Westworld’s seduction doesn’t lie within its fictional realms, but in the future of our reality.

From Aldous Huxley’s prediction of antidepressants in Brave New World to Edward Bellamy’s early imaginings of credit cards in the 1888 novel Looking Backwards, sci-fi has, on numerous occasions, accurately predicted the future. And while Westworld raises some poignant questions around the ethical implications of delving into the uncanny valley, it also hints at what the future of leisure could look like. Because, first and foremost, Westworld is a theme park.

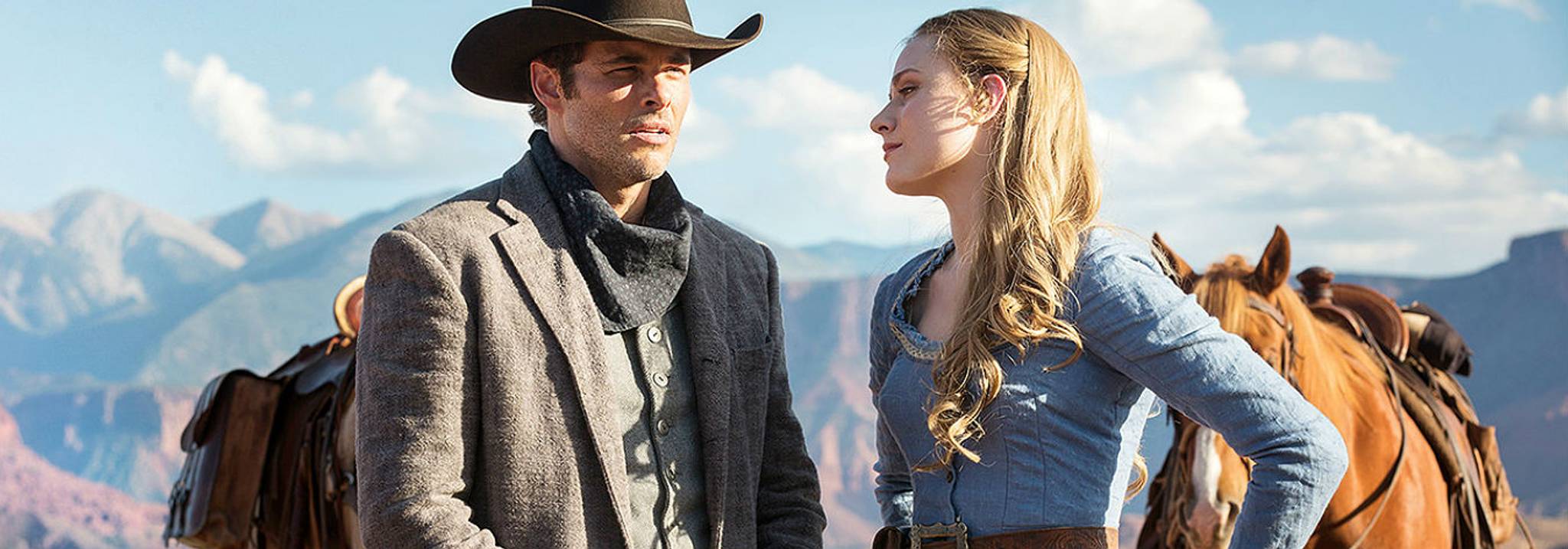

For a daily fee of $40,000, wealthy guests can immerse themselves in the Old West-themed amusement park. After picking from an appropriate wardrobe (all of which is tailored to fit), they embark on an adventure of their choosing. “The park has only one rule,” reads HBO’s promotional site. “You cannot hurt another human.” Anything else is fair game. It’s about living out your deepest fantasies, whether it’s getting the girl, killing the good guys, or anything inbetween.

The show gives human desires a dark twist – raping and killing is seemingly the norm in Westworld. But despite its cinematic license, it only builds on the escapism that’s been observed in the 19 million people that game in the real world. “A game is a box in which I understand the rules,” explains Dr. Andrew Kuo, assistant professor of marketing at Louisiana State University. “I understand how to win, and I've got a clear path in terms of how to succeed. Compare that to the real world, which is so ambiguous – what does it mean to succeed in the real world?” Similarly, each guest in Westworld seems to have their own demons to battle – their own reason for departing from reality to immerse themselves in fiction instead.

But while Westworld bears certain similarities to gaming – its visitors’ sick fascinations are easily comparable to the darkest outlets of some who play Grand Theft Auto or even The Sims – it also draws parallels with IRL leisure pursuits. Museums and art galleries are rejecting the ‘look but don’t touch’ mantra they’ve stuck to for so long, with ‘multisensory’ becoming a PR buzzword in itself. While a VR exhibit in Florida transported people inside a dream-like Dalí painting using Oculus Rift headsets earlier this year, visitors to London-based Somerset House have been able to dive into a VR world designed and soundtracked by Björk.

With 56% of people saying they’re excited by the ability to travel via VR, the chance to experience alternative realities (or simply realities that aren’t right on our doorstep) is no longer such a distant fantasy. What remains to be seen is how the ethics will play out. When asked if she’s real, one of Westworld’s bionic hosts responds, “If you can’t tell, does it matter?” It’s a question that will need to be answered when we stand on the precipice of the complicated convergence of what’s real and what’s not.

Discover more insights like this by signing up to the Canvas8 Library.

Lore Oxford is Canvas8's deputy editor. She previously ran her own science and technology publication and was a columnist for Dazed and Confused. When she’s not busy analysing human behaviour, she can be found defending anything from selfie culture to the Kardashians from contemporary culture snobs.